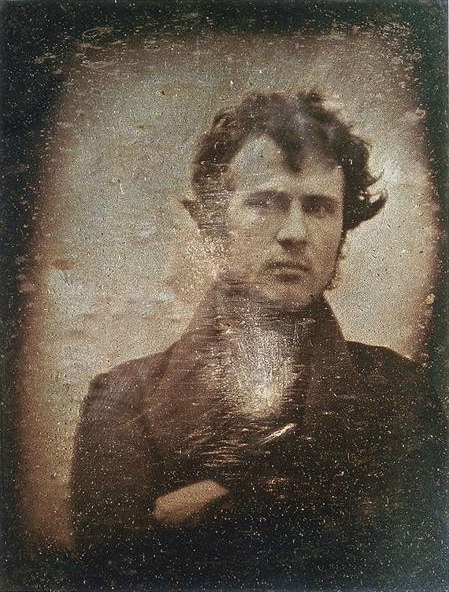

Cornelius, Robert. The First Light Picture Ever Taken. 1839. Daguerreotype.

At first glance Robert Cornelius’ self-portrait seems like an insignificant instance in time. He is the only subject against the plain, monochromatic, background. The lens is straight on, but because he ran around, he is slightly askew to the right. It is obviously experimental, the product of a curious man. When I look at the picture, I think it almost empowers him. He looks confident and he has a certain air about him. The old daguerreotype is reminiscent of a sepia-coloured selfie like the filter-laden Instagram posts you can find plastered over the internet today.

However the significance of this picture is much more than it appears. Cornelius, being an amateur chemist, was fascinated with exploratory photography. We do not perceive his portrait as “self-obsessed and tacky” (Mirzoeff. 63) like we would Instagram selfies. This is because the daguerreotype was a modern invention using the most advanced technology and science of the time, instead filtering your selfie to look aged. Photography was not readily available to everyone when it was first introduced so to take your own portrait was by no means a common activity. I doubt that his experiment was intended for any particular audience, more to quench his curiosity. However Cornelius’ daguerreotype is publicised today on the internet as a historical moment in time as the first photographic self-portrait.

Texts Referenced: Mirzoeff, Nicholas. How to See the World: A Pelican Introduction. Pages 31-69. Print.

http://publicdomainreview.org/collections/robert-cornelius-self-portrait-the-first-ever-selfie-1839/